The purchase price of an insert is only the first step in a long and complex process which eventually ends in the waste bin of worn inserts – hopefully after as many workpieces as possible have been correctly machined.

Everyone in the machining industry agrees that too much money is spent on the wrong inserts. We are all aware of the problem, but what is the solution? Most companies simply try to purchase inserts more cheaply. That is of some help, but it is not a solution to the problem. So why not opt for a more structured approach?

Some buyers often spend considerable time negotiating lower prices. The effect of this on the total production costs, however – let alone productivity – can be negligible. The purchase price of an insert is only the first step in a long and complex process which eventually ends in the waste bin of worn inserts, hopefully after as many workpieces as possible have been correctly machined.

Pragmatic study

All workshops have a collection point for worn inserts. There is nothing quite as interesting as studying worn inserts – it results in a pragmatic view of how inserts are used (or abused) and which measures can be taken to realize cost reductions. Consideration should be given to easily measurable factors:

- How many different types of inserts are used?

- How many cutting edges do the inserts

- Have on average?

- What percentage of the cutting

- Edge/edges are used in relation to cutting edge length?

- How many cutting edges are worn, broken or unused?

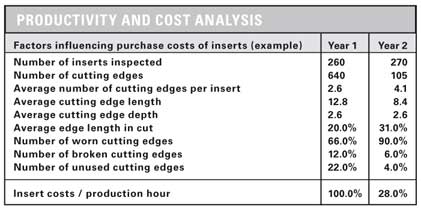

This article is based on a study carried out for a large Seco Tools customer. The results of this study are representative for similar studies regularly carried out by our company. The results of the initial monitoring are shown in the first column of the table.

Diversity of inserts

The first fact to be determined is the great diversity of inserts used. In our example, there were 638 different types of inserts to keep six CNC lathes going. The good news is that each insert is a champion in its own category. However, 638 inserts, packaged in boxes of 10, means a stock of 6,380 inserts. And all that just to keep six lathes going!

The next fact is the relatively small number of cutting edges per insert. In many workshops, a turning insert still has a triangular or rhombic shape. The possibilities offered by Trigon inserts with their optimum combination of the number of cutting edges (triangular inserts) and cutting edge strength (rhombic inserts) are apparently still not sufficiently recognized in many workshops.

The old school

During the 1970s, the best possible advice was to use large, strong inserts. The carbide used at that time was hard but not very tough. The strength of the inserts was guaranteed by their dimensions (large inserts = thick inserts = strong inserts). An insert needed a cutting edge length at least three times greater than the cutting depth. Two things have changed in the meantime. On the one hand, the average cutting depths used on turning have been greatly reduced.

A study carried out by Seco Tools indicated that the modern day cutting depth is approximately 2.5 – 3 mm for average turning work. On the other hand, modern day, fourth generation carbide – the TP2500 for example – is much tougher and at the same time much harder (wear resistant). This means that, in today’s inserts, the relationship between the cutting edge length and cutting depth can be completely different. Insert geometries of the latest generation (the MF5 for example) are clearly geared to this new situation.

Broken/unused edges

The situation really becomes clear when one looks at the inserts in terms of the way in which they have worn during use. The correct form of cutting edge wear is flank wear – safe, predictable and controllable. A cutting edge should not break. A broken cutting edge is a wrongly used, or wrongly selected cutting edge. A cutting edge must be “worn” before it is discarded into the box containing worn cutting edges. It is always amazing how many “new” cutting edges are thrown away without them ever having been used for machining purposes.

Practical tips

A number of practical tips should be borne in mind:

- Use universal and flexible inserts (for example TP2500), especially for small series production. This is a much cheaper option in the long term, than buying a variety of “specialist” inserts (remember the hidden costs such as administration, ordering and stock costs).

- Use inserts with extra cutting edges without sacrificing strength. Trigon inserts have been around for years but are still not truly appreciated.

- Use smaller inserts. There is a clear trend towards smaller cutting depths (often combined with larger feeds). Modern day carbide, especially in combination with the correct geometries (MF5 for example), can be used at a better ratio of cutting depth/cutting edge length (75% of the useful cutting edge length should be the rule rather than the exception). And consider the price difference between DNM.11 and DNM.15 inserts!

- Make sure the inserts wear correctly (flank wear, possibly in combination with crater wear). Inserts must not break. Think of the consequences: irrevocable damage to a workpiece and/or machine equals loss of production with associated costs. Finally, each insert purchased must be used and not thrown away beforehand. Schematic-based problem solving can be very helpful.

Conclusion

In the study referred to in this article, Seco in close co-operation with the customer, has proven capable of reducing the insert costs per production hour by more than 70%, by applying three measures: on average, more cutting edges per insert, smaller inserts and less broken or unused cutting edges. And that’s not exceptional! Clearly, such measures must be accompanied by effective supervision and training of the people involved. In fact, that is possibly the key; training is required in order for people to have a better insight into machining and how a cutting edge works.

The icing on the cake is that employees become more involved in the machining process as a whole. They will then introduce their own ideas for improvement, resulting in a self maintaining process of consistent improvement. After this initial step we can get down to the serious work and introduce measures that will help increase your productivity and reduce your production costs significantly.

By Patrick de Vos, Global STEP Master (Seco Technical Education Programme), Seco Tools. Patrick has led the creation of STEP (Seco Technical Education Programme) and has the global responsibility for technical education activities for SECO employees and customers worldwide.

By Patrick de Vos, Global STEP Master (Seco Technical Education Programme), Seco Tools. Patrick has led the creation of STEP (Seco Technical Education Programme) and has the global responsibility for technical education activities for SECO employees and customers worldwide.

E: patrick.de.vos@secotools.com